Mahler in the netherlands

In 1902, Gustav Mahler met the young conductor Willem Mengelberg, marking the beginning of a close friendship and a strong Mahler tradition in the Netherlands. Mengelberg introduced Mahler's music to the Concertgebouw Orchestra, where the composer himself conducted several works. Thanks to Mengelberg and composer Alphons Diepenbrock, Mahler felt at home in the Netherlands, his "second musical homeland". Their collaboration left a lasting impact on Dutch musical culture.

Introduction

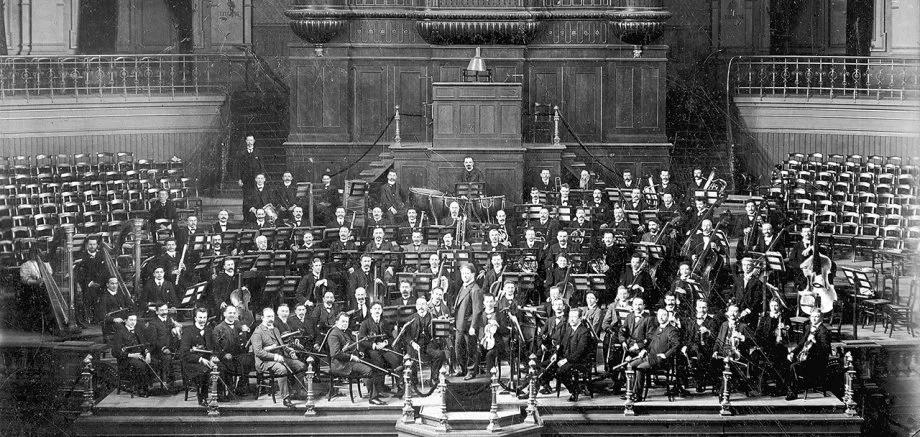

For the Concertgebouw Orchestra

So it all began in 1902 in Krefeld; what an encounter that must have been! "Without yet knowing him personally, I attended the concert," Mengelberg recalls, "and was immediately impressed by the fascinating power emanating from him.

In his interpretation, in his technical treatment of the orchestra, in his way of phrasing and construction, I found everything that I - as a young conductor - had in mind as an ideal. And so when, after the concert, I met him in person, I was deeply moved by his music: I promised to have him perform the work in Amsterdam as well as soon as possible.

I realised that the evocative power of the composer himself would be of great importance for the understanding of this completely new artistic expression and so I proposed that he come and introduce the work to us personally". And so it happened: Mahler seized the opportunity with both hands.

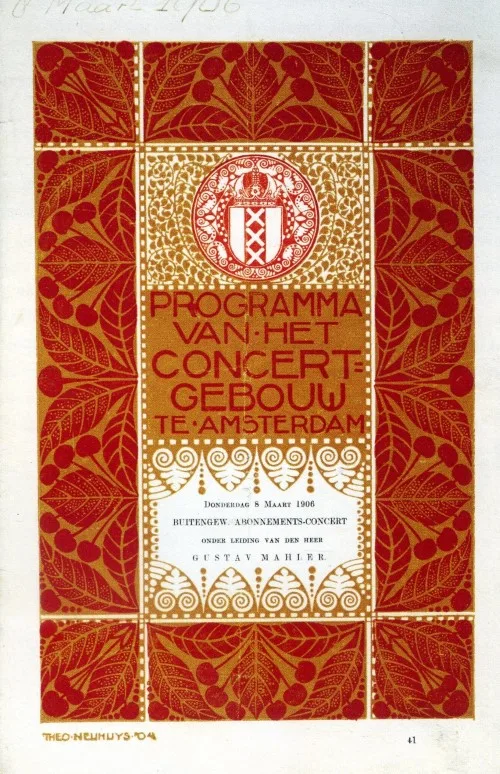

He first set foot on Dutch soil in the autumn of 1903, to conduct his Third - and in a later concert, his First symphony - at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. Mahler was pleasantly struck by the outstanding quality of the orchestra and the way Mengelberg had rehearsed the symphony.

"The general yesterday was wonderful," he writes to his wife Alma on 22 October. "Two hundred schoolboys led by their teachers (six of them) roared the bim-bam and there was a magnificent women's choir of a hundred and fifty voices! Orchestra magnificent! Much better than in Krefeld. The violins as beautiful as in Vienna."

This must be just about the highest praise Mahler could give others. all the collaborators clapped and waved without ceasing. "The music culture in this country is astounding! The way these people can listen."

What did the orchestra itself think of it? "For all staff members, the way he performed his music was extremely interesting and instructive," Mengelberg said. "Especially his rehearsals laid the foundation for our entire continued practice of his art.

Das Wichtigste steht nicht in den Noten. This was the guiding principle of his creating and also of his interpreting. And he did not tire of repeating it again and again and applying it in practice. At rehearsals, he was extremely spirited.' This characterisation did not only apply to rehearsals, by the way. Mahler was known to friend and foe alike as someone who did not mince his words and demanded the utmost from himself and those entrusted to him, be it his wife, the Hofoper or a guest orchestra.

Hotel Mengelberg

Egg of Columbus

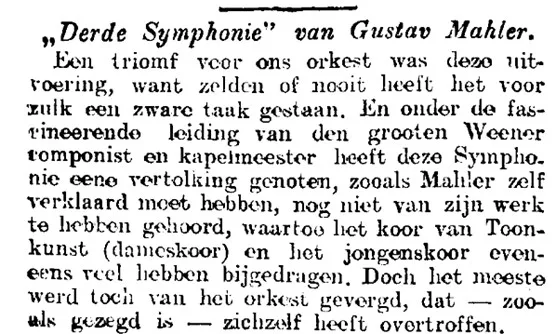

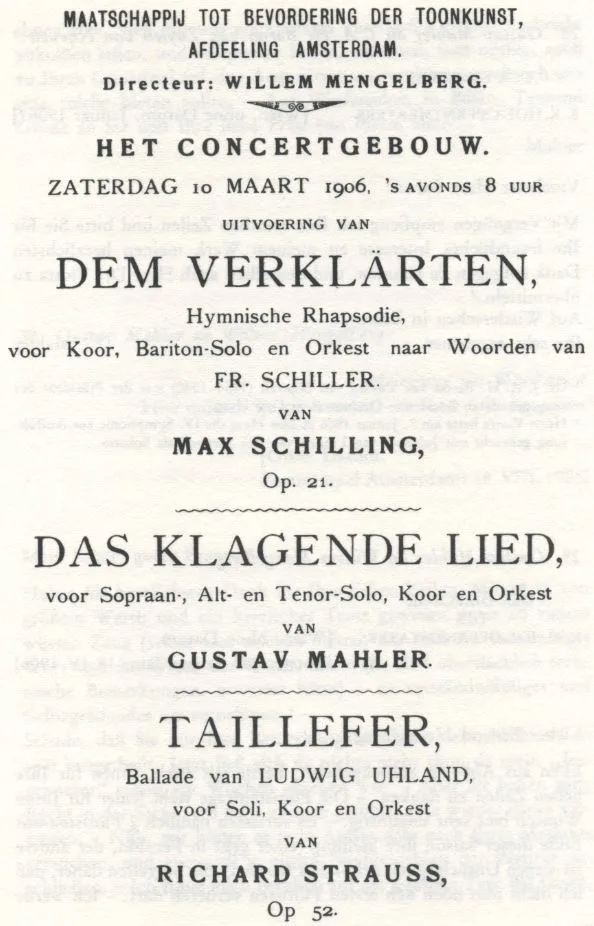

Pièce de résistance of this October 1904 sojourn, however, is the Second symphony, whose choral rehearsals had already taken place while working on the Fourth. According to Mahler, the choir sang beautifully. Indeed, according to Mengelberg's recollections, Mahler found a "serious and enthusiastic co-operation" with the Toonkunst Choir.

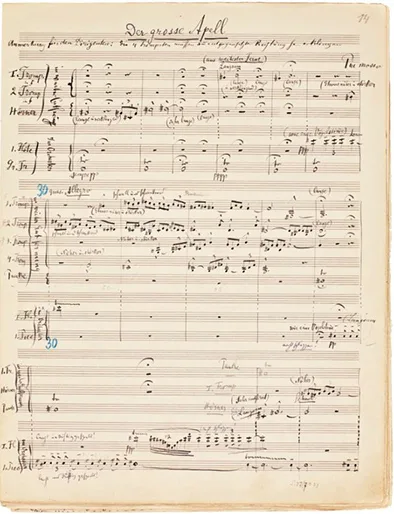

Mahler gives the duration of this symphony to Mengelberg as an hour and a half, in contrast to the approximately three-quarter-hour Fourth, which therefore very well tolerates another, or the same, symphony on the programme. Even before he travelled to Amsterdam, Mahler had already urged Mengelberg to give him an extra rehearsal for 'der grosse Apell' (one of the most (in)exciting moments of the Second's finale) in order to properly coordinate the Fernorchester with its four trumpets, four horns and timpani and the hushed separate flute and piccolo on stage.

To this day, it has not been handed down how Mahler got those two orchestras throbbing. After all, there was no television back then. Perhaps the door to the corridor was wide open, and brass players lurked around the corner, or maybe there was an assistant conductor in the corridor.

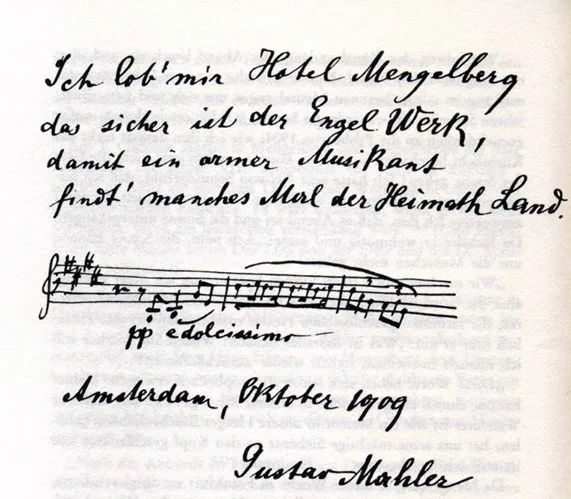

Also, mindful of the clean wall decoration in Van Eeghenstraat, he raises the lodging problem: "Do I really have to tease your wife with my presence again. I think I will quietly go to a hotel (but in a quiet room) and make sure to be with you as much as possible; doesn't that seem best to you?" As if sensing that Mengelberg might feel hurt by this, he adds in a postscript: "I only want to go to a hotel because I don't want to be a burden to your wife - after all, I felt like a brother with you last year." Of course, the Mengelbergs don't let something like that get to them; they pick him up from the station and don't rest until Mahler goes with them!

Magic power

The little-great tyrant

In his reply, Mengelberg says he is very disappointed, but that period is too late for his audience. To Mahler's proposal to then introduce the Sixth without him, Mengelberg responds dismissively: "I want nothing more than for you to conduct the first performance yourself." So it is not until 1909 that Mahler sets foot on Dutch soil again, for the last time in his capacity as conductor. He then brings with him not the Sixth, but the Seventh symphony. This score is still in the possession of the Concertgebouw in manuscript, gifted to Willem Mengelberg by Alma.

Meanwhile, much has happened: the year 1907 turns out to be a year of disaster. Not only does Mahler have to resign as musical director of the Hofoper, but catastrophes also occur on a personal level: his eldest daughter dies of a combination of scarlet fever and diphtheria and he himself turns out to suffer from double heart valve insufficiency. Mengelberg marvels at the dismissal but says Mahler will have his reasons for it.

Their correspondence shows that there is then still talk of some concerts - with the Sixth - in January 1908. But as mentioned, the Sixth does not come and neither does Mahler. Similarly, Mahler's attempts to get Mengelberg to Boston fail (despite the tempting offer of a generous salary): Mengelberg remains in Amsterdam. There, the friends-colleagues will then meet for the last time in October 1909.

In June, Mahler writes to Mengelberg that he is available from 3 October and that he will come not with his Sixth, but with his Seventh. Again, he urges Mengelberg to prepare the symphony so well already that two or three rehearsals will suffice. Like the Fifth, this work also lasts five-quarters of an hour. "You can programme a short Haydn or Mozart symphony for that, but you have to conduct it yourself. That saves me rehearsal time." Furthermore, he is hugely looking forward to seeing his Dutch friends again and - as always - staying at the Mengelberg home.

On 27 September, Mengelberg gets Mahler off the train. The next morning is the first rehearsal under Mahler's direction: "Everything again beautifully prepared," he writes to Alma, "It sounds fantastic". So his urgent request to his colleague clearly bore fruit. Indeed, Mengelberg had spent a week under high tension rehearsing the orchestra morning and evening.

"I can't remember a work ever being rehearsed with such precision," he said.

recalls one of the then orchestra members. But then Mahler came and immediately it was a hit. At the first rehearsal, he criticised the dedication as rehearsed by Mengelberg. Loyal as the orchestra was to its chief conductor, things threatened to escalate, but fortunately Mengelberg's presence at all rehearsals acted as a catalyst: an impending revolt was averted.

The orchestra member is full of praise for Mahler as a conductor: "He was a great master, almost motionless he conducted his symphony and led the orchestra more with his eyes than with his right hand. Mahler played with the orchestra, as it were, and every musician felt that he had to play his part in the way the little-great tyrant forced him to."

Prophetic were the words Mahler uttered while walking along the Scheveningen beach. Oppressed by the already setting sun and the prevailing sea flare, he spoke:

"How ugly it all is. You know, I never want to come back here again in my life."

Indeed, this beach no longer received Mahler's footsteps; that privilege was reserved for the pavement of Leiden's Breestraat, where the legendary meeting between Mahler and Freud took place.