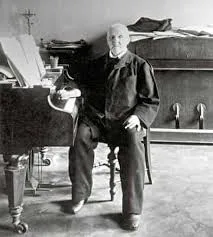

Mahler in his time

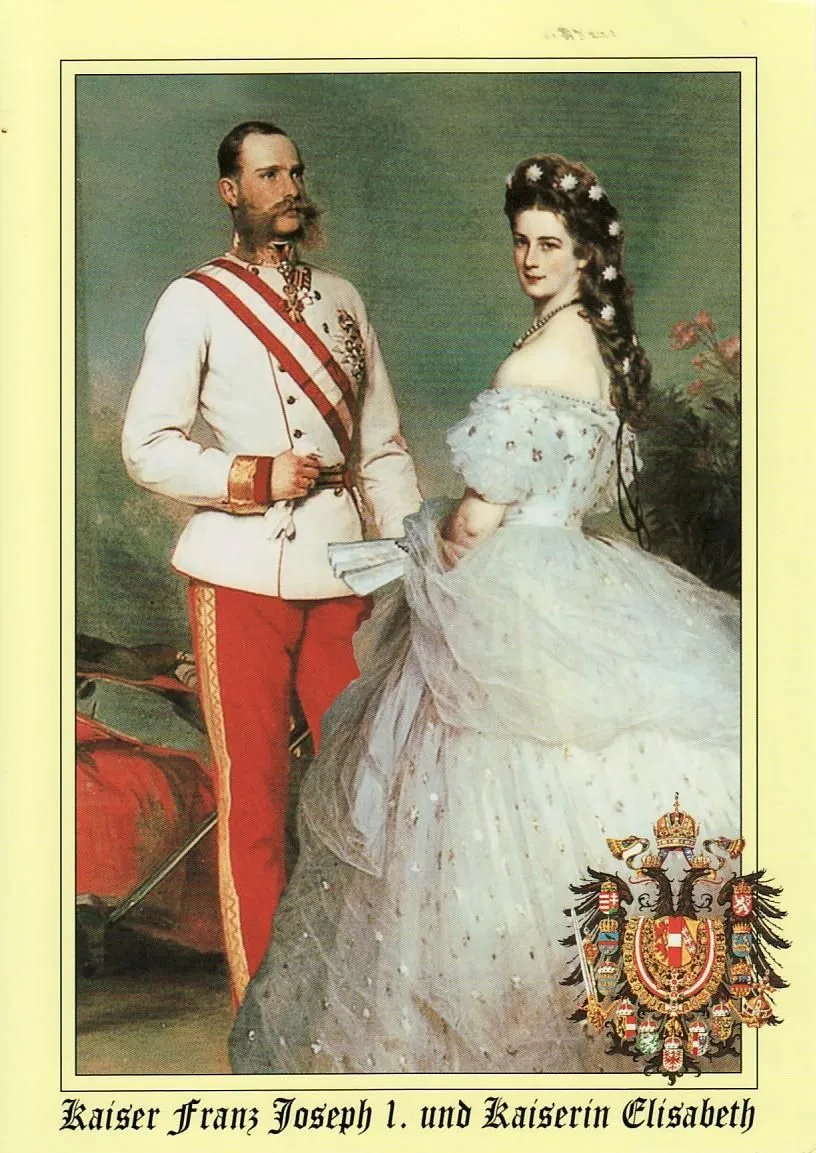

Vienna around 1900 was a vibrant centre of culture and innovation under Emperor Franz Joseph. Gustav Mahler, a bridge between romanticism and modernism, was influenced by Wagner and Bruckner and was in dialogue with Strauss, Schoenberg and Wolf. In Vienna's salons and Kaffeehäuser, art, debate and philosophy flourished. Amid religious and social changes, Mahler found his unique musical voice, which resonates to this day.

Introduction

The Bildungsbürger

The Secession

Philosophy and religion

Mahler as trait-d'union between romantics and modernists?

Mahler and his contemporaries

Mahler's admiration for his teacher could sometimes take a form that we now interpret not so positively. First of all, when Mahler had the honour of giving Bruckner's Sixth Symphony its world premiere in Vienna, Mahler picked up a red pencil and started to shorten the symphony considerably! Bruckner, by the way, would not have been surprised by that. As a doubter of his own creativity, Bruckner was used to revising his own work and also allowed benevolent conductors to polish his pieces. Mahler, unlike us now, did not see his interventions in the score as a detriment to Bruckner's music, but rather as an attempt to make the music better. Admiration for his teacher was his driving force.

He also took Bruckner's Fourth Symphony in this way. For that reason, he also polished symphonies by Schumann and Beethoven.

Mahler showed his admiration for Bruckner early on. As a test of competence, by way of an examination, he had made a piano excerpt of Bruckner's Third Symphony with a conservatoire colleague. In it, he did not change a single note of the symphony. That extract was so good that it even appeared in print in 1880 and was even given a place of honour in Mahler's study. When Alma wanted to flee from Vienna across the Pyrenees to America after the Anschluss in 1938, it was imperative that she took it with her and lugged it along in a heavy suitcase.

Hugo Wolf

Richard Strauss

While Wolf was only of equal calibre in the songs, Richard Strauss was so on all fronts. Although they were only four years apart, there is a world of difference between these two representatives of the late-nineteenth century. Strauss (1864-1949), a Catholic, seemed to have everything in his lap; Mahler, a Jew, had to fight for everything. Both wanted to reach the top as composers and conductors, and both succeeded. For a long time, their paths as composers ran parallel.

Strauss' 'hobbyhorse', the symphonic poem, also initially found an audience with Mahler and he even composed a symphonic poem of his own, Totenfeier, which, in slightly reworked form, would later become the first movement of his Second Symphony. On the concert stage, they performed each other's works from the outset, adhering to the motto: 'If you put a work of mine on the programme, I'll do a piece of yours at the next concert!' Mahler's big breakthrough with his Third Symphony was partly due to the fact that Strauss selected this work for the 1902 Music Festival in Krefeld. Until his death, Mahler repeatedly Tondichtungen - as Strauss called them - performed, in America as many as 11 times Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche. Strauss in turn occasionally conducted works by Mahler.

Mahler also wanted Strauss' opera Salome perform, which he said was one of the masterpieces of its time. Unfortunately, Mahler had not taken censorship into account in doing so. We should not forget that Austria was very Roman Catholic and that it is an opera in which morals are very much trampled upon and in which a head is carried in on a silver platter and even that of a prophet. That was definitely a bridge too far for many a moralist in 1905.

Strauss soon learned about it in the Kaffeehaus (the customary place to hear the latest news), was unpleasantly surprised and spoke to Mahler about it. The latter exhausted himself in apologies, but had to admit that it really was 'the sad truth'. 'The censors have since Salomedenied. So far no one knows, but I am trying heaven and earth to reverse this decision.' Mahler appreciated the free spirit expressed in the work.

This persistence against the odds also had a musical reason: 'Dear Strauss, I must tell you how thrilled I am with your work, which I recently reread. It is your highlight so far! Yes, I claim it cannot be compared to anything you have written so far. Here every note is in its proper place; you are a born dramatist.' But all this praise notwithstanding, the gentlemen would fail to Salome to be premiered in Vienna and thus not under the baton of Mahler, who had oh so much wanted it. Despite this disappointment, Strauss continued to hold Mahler in high regard. After Mahler's death, he wrote a stirring memoriam in a letter.